I hope that everyone is enjoying the spring recess so far!

Since we didn’t meet for class today, I wanted to update you all on the remaining opportunities you have to improve or demonstrate your mastery of the Four Capabilities, which is the sole thing that I will be looking at when assessing your final grade for the course.

You have now received all of the required writing-based-on-reading assignments, which are collected under the Reading Questions category.

Over the next week, I will be catching up on giving you feedback on any assignments I have not yet read and commented on. By April 7, I will be caught up, and after that there is one more required writing assignment for you to do. You will need to write a self-assessment of your own learning progress in the course that uses (a) the principles outlined in the rubric and (b) specific evidence from your own work in the class to justify your conclusions. This final assignment will be due by April 22 (the last day of classes for the semester). This self-assessment should be written in complete sentences and paragraphs, and should be about the length of one of your usual reading responses. It needs to be guided by all the same principles of Position Taking and Effective Communication that should guide any piece of writing in this course.

In addition to that final required writing assignment (and your group’s work for our presentation), you also have some optional things you can do if you have not yet achieved mastery of the Four Capabilities and want to show me continued progress on the rubric.

First, you can revise and resubmit up to two of any of your previous assignments in the Google Doc. Just write the new version at the bottom of your Doc and clearly indicate that it is a revision. As long as I receive these by the final day of final exams, which is May 4, I can consider them when making a final assessment of your mastery of the rubric. Keep in mind that these revisions only help you on that score if they in fact show improvement in the areas that you and I have already flagged as needing improvement, so I’d encourage you to talk with me about planned revisions, but that talk, too, is optional.

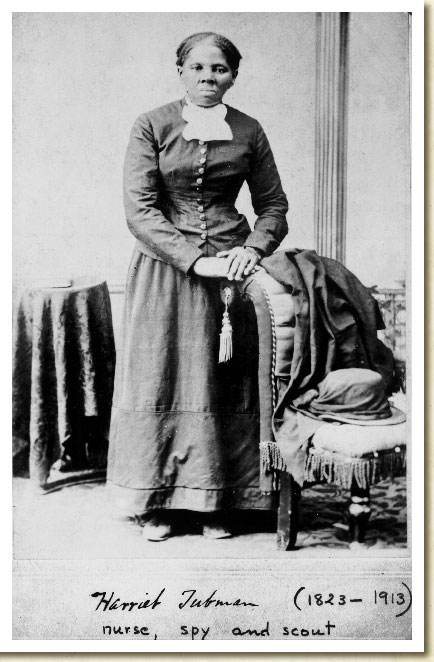

Second, you can write an optional position-driven essay based on material in one of the "extra" posts I have published on this blog—that is, posts that were not about the assigned weekly readings. These include a post about a controversial children’s book on Washington and slavery, about controversies over Woodrow Wilson at Princeton, about Presidents’ Day and the use of Presidents in election cycles, about some news items on figures we’ve studied, and about my four-year-old daughter’s perceptions of two legendary Americans. (By the way, I swear she picked out that John Henry book from the library on her own. I didn’t put her up to it!)

I’m giving you considerable flexibility with this assignment, but you need to tell me the scenario you are writing in (the form of writing, the audience, etc.) yourself and make sure that you are taking a position. The audience could, of course, just be me, and you can treat this essay much like a standard reading response. But if one of the areas you need to work on is audience awareness, it might be in your interest to think about how you could use the assignment creatively to show progress on that skill.

Because of these optional assignments, you have no shortage of ways to show that you have mastered the Four Capabilities by the end of the semester. But remember that because of the way your grade will be assigned, simply doing these optional assignments doesn’t immediately give you extra credit. The optional assignments help you improve your grade only insofar as they help to demonstrate your mastery of the rubric.

While you’re working through Scott Reynolds Nelson’s book this week, you may enjoy listening to some versions of the John Henry ballad

While you’re working through Scott Reynolds Nelson’s book this week, you may enjoy listening to some versions of the John Henry ballad  Hope you all had a good Spring Break! This week’s reading, listed on the

Hope you all had a good Spring Break! This week’s reading, listed on the